In Conversation

Jamie Woods doesn’t write poetry for your comfort. He writes because he must—because the words arrive heavy, vital, unfinished until spoken aloud. “I’ve always written: lyrics, reviews, short stories, opening chapters to novels, and poems,” he says. But it’s poetry that stuck. Not for lack of ambition elsewhere, but because it’s the only form that lets him finish things. No guitars. No 80,000-word marathons. Just language, distilled and detonated.

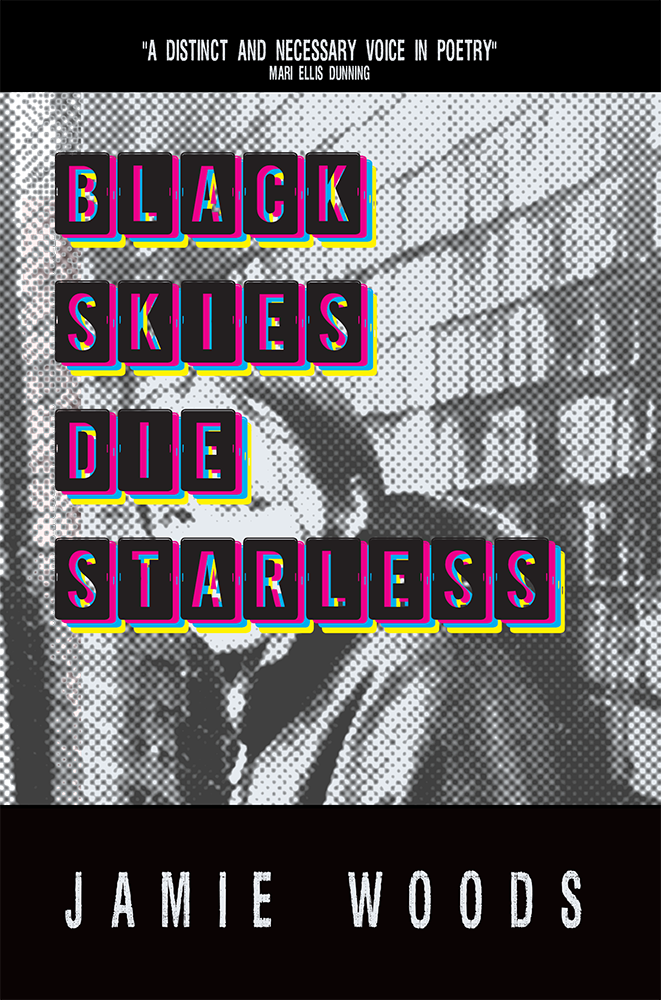

A writer from Swansea, Woods has been published in Poetry Wales, iamb, Lucent Dreaming, and more. His voice, grounded in illness, protest, and personal reckoning, stands fiercely apart from the manicured lyricism of the mainstream. As Poet in Residence at Leukaemia Care UK, his work bears the emotional reality of disability, grief, and survival. His chapbooks Rebel Blood Cells and Black Skies Die Starless, both released by Punk Dust Poetry, cement his reputation as a poet who doesn’t flinch from the uncomfortable. He leans into it.

Woods’ poetry sits in the awkward, necessary gap between the personal and the political, where grief is public and protest is personal. His latest collection revisits the 1990s not to bask in neon-drenched nostalgia, but to crack open the decade’s hypocrisies. This isn’t just cultural commentary. It’s emotional archaeology.

What draws Woods back to the page is poetry’s capacity to compress—emotion, memory, devastation—into something sharp enough to carry. He cites Andrea Cohen’s “The Committee Weighs In” as proof of poetry’s devastating minimalism: “In just 8 lines she conveys so much emotion: pride, grief, trauma, loss.” It’s this aesthetic of impact, of poetic smallness with emotional gravity, that fuels his own work.

Take his poem “Sleep”. Born from a wrecking dream, it channels loss and love into what he calls a “bubble” he could wave off into the world. “Cohen’s is a better poem in terms of conciseness,” he admits, but his is soaked in a personal dreamscape. Both hit. That’s the point.

There’s no ritual in Jamie’s writing. No candlelit desk or 5am clarity. Inspiration comes fast and loud: an angry meme, an old song on loop, a line that refuses to leave his head. He writes in email drafts, in midnight phone notes, often in protest. “There’s no physical setting… just inspiration.”

But make no mistake, there’s craft. Instinct births the poem, but editing is where it lives. He carves carefully, thinking about syllables, sound, and performance. He even edits to avoid sounds that don’t serve him on stage: “I have a self-conscious sibilance issue so I typically avoid writing poems with heavy S’s.” This is poetry as both text and performance, shaped by mouth as much as mind.

Woods’ literary compass is blunt and eclectic. Patrick Jones is a spiritual North Star: truthful, direct, and unwilling to flinch. Larkin, the “problematic bae,” still lingers as a technical influence, even if his legacy is fraught. And Richard Gwyn’s “Dusting” didn’t just move him, it “set a course and changed my life.” Poetry, for Woods, is never detached. It hits or it doesn’t. And when it does, it alters something elemental.

The heart of Woods’ new collection beats against the grain of pop-cultural nostalgia. Where others see Britpop and good vibes, he sees exclusion, unspoken damage, the long hangover of a society learning the wrong lessons.

In “The Perpetual Illusion of Progress”, Woods swings between dated optimism and present-day cynicism. “We’re still doing the same things today and we need to stop,” he says. The poem stayed in the collection precisely because it’s uncomfortable—it breaks the spell of 90s revisionism with something harder, rawer. It’s political, but also deeply personal. The decade didn’t give him a soundtrack. It gave him scars.

“I don’t care about flowers or plants or the wisp of hair on a baby’s head,” he says. What he does care about is using his voice, his privilege, to speak when others can’t. “I should as a matter of principle use my platform to lift others.” There’s no judgment for those who don’t write political poems. But for those with power? There’s an expectation.

Woods’ relationship to the poetry world is ambivalent. He sees himself as “on the outside, looking over the fence.” But his work has been championed by patients, outsiders, the people who don’t always get a poem written about them. He may not be in the Faber circuit, but he’s built something real, and perhaps more vital.

Woods recalls a brutal rejection letter, notable mostly for its Cardiff University slander and its commercial cynicism. But the good part stuck: “make the personal universal.” That advice reshaped his work. Now, if a poem doesn’t say something wider, if it doesn’t invite others in, it gets rewritten or binned. The ego, in Woods’ practice, doesn’t get the final say. The reader does.

What Woods is wrestling with now isn’t just subject matter: it’s delivery. He wants to read more, perform more, bring video and music into the mix. He wants his poems to sing. The barriers are real: health, fatigue, and travel… but the desire is louder.

And thematically? He’s after the holy grail: “how to make the political poetic, without the perennial naffness of polemic.” It’s protest with rhythm, rage shaped into resonance.

For Jamie Woods, poetry is never done. It evolves with context, with time, with each reading. Like a song rearranged, the same poem can carry new weight in a new world. He writes with urgency, edits with care, and performs with a clear sense that words can bruise and build in equal measure.

In an era obsessed with clean narratives and soft landings, Woods reminds us that poetry can, and should, bite. That it should question, not confirm. That it should say the hard thing, even if it never gets you invited to the literary dinner table.

Read his work. Let it mess with you. That’s the whole point.

In Critique

Jamie Woods’ Black Skies Die Starless is a text defined by disintegration: linguistic, emotional, cultural. Its formal tension lies in how often it abandons the illusion of control while still being acutely composed. Across the collection, lineation functions as emotional register. Spacing, enjambment, fragmentation all operate to recreate the uneven breathing of grief, the psychological clutter of adolescent memory, and the simmering volatility of disillusionment. This is not poetic nostalgia. It is a forensic audit of it.

The opening poem “The 90s” lays the groundwork. It is structured as anaphoric chant, each line ending with the refrain “in the 90s.” This repetitive architecture mimics mantra, advertising jingle, political slogan. It satirises each. The poem is list-based, but the items chosen are pointed: “Prozac,” “bacterial infections,” “second-hand bands.” These are not the props of carefree youth but of malaise thinly veiled by culture’s flash. The choice of punctuation, complete absence, accelerates the pace and denies the reader rest, formally mirroring the breathless, unprocessed trauma underneath the pop-cultural detritus.

What is striking in Woods’ strongest poems is the interplay of line and image. “Swinging” exemplifies this. It opens in narrative mode—reminiscent of prose poetry—but quickly fractures under the weight of accumulating chemical names and adolescent bodies choking on toxicity. The list of substances moves from the vernacular to the grotesque: “shoe polish, barbiturates, aspirin, pine resin, beeswax, shellac, oregano and turpentine.” The absurdity builds pressure. Rhythm here mimics paranoia. Syntax is stretched until it flicks back into control with the refrain “we swing back and forth,” a phrase that physically and metaphorically enacts instability. Woods allows form to do what narrative cannot: hold contradiction without collapse.

In “Atrophia,” he tests a split-line structure, bifurcating the voice. Each line begins with declarative external action, then brackets a whispered, internal collapse. The formal duality reflects disassociation. The language becomes tactile: “forced to accept just what I am (fractured skin) (scarred and calloused).” The poem does not rely on metaphor. It relies on accumulation of physical details and restraint. The parentheticals serve as phantom thoughts, slipped in rather than shouted.

Woods shows equal formal discipline in “Unread Seroxat (Paroxetine) Patient Information Leaflet.” Here, the poem mimics the staccato of pharmaceutical caution, subverting the cold rationality of dosage notes with emotive despair. “Numbs every emotion / only emptiness.” The lineation is taut. The poem short-circuits itself emotionally. The lack of rhetorical flourish is a formal decision. That restraint is not minimalist. It is diagnostic.

His engagement with music is more than decorative. Each poem ends with a band and track title. Initially, this risks feeling like ephemera, an attempt to cement cultural reference. But it becomes clear that these songs scaffold emotional memory. In “The Perpetual Illusion of Progress,” a sprawling social commentary on 1990s politics and media, the paratextual note: “Sonic Youth, Swimsuit Issue, Geffen, 1992” tethers the poem to a specific sonic angst. The poem itself is a cascade. Clinton’s saxophone, tabloids, Wonderbras, Hayley Cropper. This is cultural critique as floodplain. The structure flirts with collapse. What rescues it is precision. The shift from litany to moral indictment is controlled. “Because when they say our own it does not include us.” A line that punches because it arrives after overload.

Not every poem avoids indulgence. “Manic Pixie Dream Boy” probably leans too heavily on trope, its emotional weight carried more by its concept than by its craft. Lines like “part my hair to the side to look like you” echo earlier moments but lack the compression found elsewhere. Similarly, the song-title framework sometimes does more work than the poem itself. These are rare but revealing slips, places where tone outpaces tension.

Woods understands that the voice of a poem must be more than confessional. It must be architectural. His poems do not spill. They are laid brick by brick, even when the subject is collapse. He uses enjambment to provoke not just rhythm but meaning. Syntax does not just express but withholds. Most importantly, he recognises that form is not something applied to content. Form is content. The way grief stammers, the way protest accumulates, the way memory corrodes, these are all structural realities as much as emotional ones.

This is poetry that remembers without forgiving. It rewires adolescence as something toxic and luminous. Woods does not write about the past. He dissects it. Not to pity it. To expose it. And in doing so, he demands his reader reckon with the same ghosts. Formally, that is what the best of these poems achieve. They do not ask to be admired. They insist on being understood.