A Promote Indie Lit Article

In Conversation

Karen Pierce Gonzalez doesn’t just write poems — she builds bridges between worlds.

From the moment she first read nursery rhymes in elementary school, she’s been walking that bridge. Dr. Seuss opened the door to playfulness; folk ballads taught her story; ee cummings handed her linguistic courage; and Joni Mitchell showed her how to lace the ordinary with magic. “It’s part of my DNA,” Gonzalez says. Poetry isn’t a pastime for her, it’s wiring.

Her writing life is less about chasing inspiration than about tuning herself to receive it. She talks about aligning body, heart, and mind so that when the poem arrives, she’s all there. Sometimes that means fast, breathless drafts. Other times, a slow simmer. Always, it’s about listening to what the poem wants: when to dive in, when to walk away, and when to circle back.

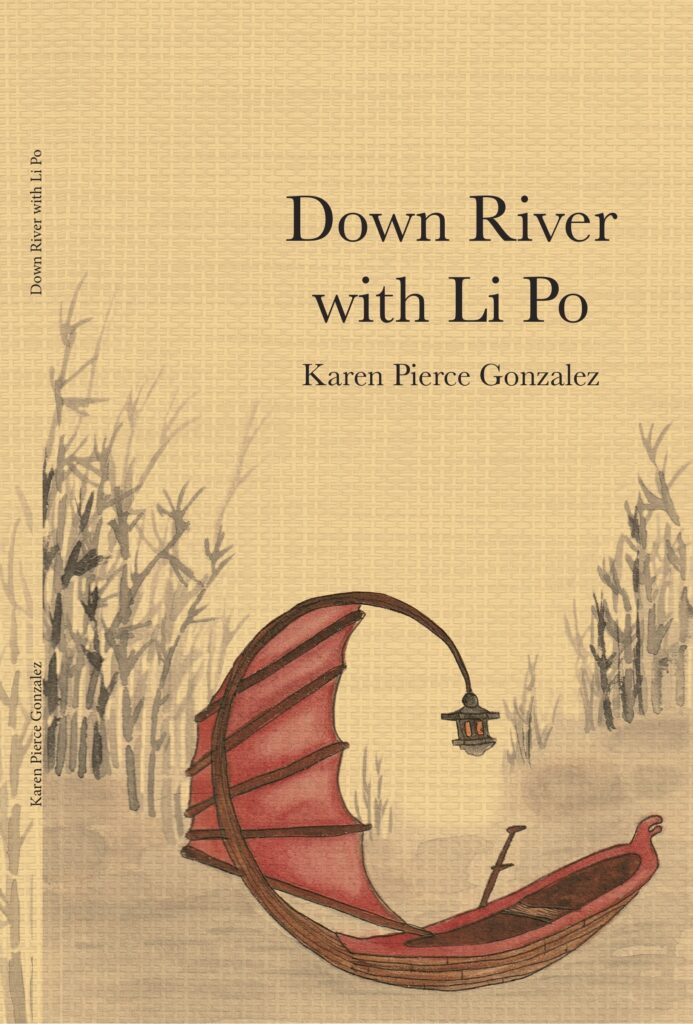

Her influences read like a mixtape of lyric bravery: cummings, Mitchell, Li Po, Rumi, Lucille Clifton, Joy Harjo. Her latest collection, Down River with Li Po (Black Cat Poetry Press), is a love letter to that lineage… and a conversation with it. She steps into Li Po’s moonlight not to imitate him, but to stand beside him, exploring how our connections to the natural world are both deeply personal and shared.

That care extends to curation. Not every poem makes the cut — and that’s by design. She talks about honouring the “inherent rhythm and pace” of a collection, creating space for the reader to breathe. If a piece doesn’t serve the journey, it stays on the bank.

Her process is a dance between instinct and craft. “you cannot sculpt a piece of ice until the water has frozen” she says. First comes the heartbeat: the raw, instinctive centre. Then comes the shaping, the honing, the labour that turns feeling into something “recognisable, relatable.” Revision is where she tests herself: Does the poem sing? Does it sting? Does it stand on its own without her to explain it?

For Gonzalez (like myself), poetry isn’t just art: it’s truth-telling. That truth can be gentle or sharp, imagistic or critical. It can take the form of a grasshopper’s leap or the hard edges of social commentary. What matters is the courage to follow where the poem leads.

She’s a connector in the poetry community, able to slip between different circles and give as much as she takes. And she’s humble enough to let good editorial advice change her mind, even when it means cutting a “brilliant” piece for the good of the whole book.

Right now, she’s “dancing intuitively” with the urgent issues that move her: racism, sexism, classism. She’s not wrestling with them. Rather, she’s stepping in with purpose and grace, letting the work carry both the joy and the fire.

Karen Pierce Gonzalez writes with the conviction that poetry is for living in, not just reading. She offers her readers the joy of counting stars, feeling the wind, watching lovers greet each other like it’s the first time — and the courage to face the darker truths without looking away. In her hands, poetry becomes exactly what it should be: a bridge worth crossing.

IN CRITIQUE

That openness in conversation mirrors the openness in her work: an invitation to read not just the finished poems, but the process, the bridges she’s building in real time.

Down River with Li Po (Black Cat Poetry Press) is a lyric correspondence across rivers and centuries: the speaker tracks Li Po’s moon-drunk poise through Californian weather, testing whether inherited images can still carry ethical and emotional weight. Formally, the book is built from short-lined, heavily enjambed pieces that favour crystalline nouns, personified cosmos, and quick voltae. At its best, the work makes the Tang inheritance feel lived-in and local.

Structure & lineation

The collection opens in direct address and ends in reconnaissance, framing a journey from homage to self-authorship. “On the bank” establishes the book’s engine: short, pressure-bearing lines, plain diction, and a willingness to name the old master without coyness, “Face pressed against the porous willow weave of time / I watch Li Po write.” The poem moves on caesural pivots (“Boar bristle brush in one hand, wine cup in the other,”) and ends with an earned miniaturism, “Snow falls.” that reads as a quiet signature, not a cliché, because the preceding syntax has done the descriptive labour.

Across the book, line breaks serve breath and hinge the image: “Lunar lips sealed, / she cannot swallow even one sip. / I drink her share and dance.” The lineation keeps the personification taut and allows the comic beat of “I drink her share” before the verb “dance” tips the tone from devotion to play. By contrast, where lines become list-like, the music can thin. “Soul birds”—“Wild geese in formation / protect the world.”—pushes toward proverb.

Sequencing traces seasons and urban/rural shifts (winter wells, spring lanterns, summer ripeness, autumn slippage), which gives the work an unobtrusive macro-architecture. “Waiting” starts in winter austerity: “Winter wraps around / the well / rimmed with white frost.” while “The shift” tips the year with a physical stumble: “Foothold gone, / knees scrape against autumn.” The body marks seasonal time; thankfully, the metaphor is kinetic rather than ornamental.

Diction, imagery, rhythm

The book’s diction is tactile and tool-forward: “rice paper,” “boar bristle brush,” “porcelain,” “paddle boat,” “webbed feet,” “kiln.” This craft vocabulary grounds the celestial tilt. In “Merlot with the Moon” the sky is stitched like a quilt: “Patchwork planets and constellations / … pieced together with irregular threads / of light” — a domestic metaphor that reframes cosmic scale in human hands. The meter is largely free which helps the poems accrue through image rather than argument.

Birds and water are leitmotifs, sometimes generative, sometimes familiar. “Dawn winds / blow down the Yangzi River / merge with the Russian River of my home” — the merger is a clean, formal way to declare the project’s doubleness; the subsequent metamorphosis from trout to hawk: “side fins spread into the rich plumage / of a red-shouldered hawk” gives the image a surprising torque rather than a neat equivalence. Elsewhere, hawks, geese, jays, swallows proliferate; where the poem provides behavioural specificity (the “ruby-crowned Kinglet / hops up and down… / Small body spins.”), the image earns its keep; where birds carry abstracted “goodwill” they feel like symbols on autopilot.

Tonal control is generally poised. The book can handle humour without deflating the lyric: “I drink her share and dance. / Clumsy, drunk shadow sways.” reads like a wink at Li Po’s legend as much as a genuine toast. It can risk sentiment, “rose gold currents / soften even the stones.”, which, taken alone, lean decorative; yet within “During the invasion,” the line contrasts with the siege’s harsh consonants (“Panic punctures my sleep, / dread pierces my dreams.”), and the alliterative patterning (“p…p… / d…p…”) gives the stanza a musculature beyond its gentleness.

Intertextual strategy & intent

Gonzalez declares her debts explicitly: several poems are “Inspired by… public domain translations” of Li Po, with clear pairings (e.g., “Merlot with the Moon”; “Amidst the Flower – a Jug of Wine”). This is not ventriloquism by stealth; it’s an open compositional method. Where the adaptation succeeds, the poem relocates the scene rather than merely renames its props. “Merlot with the Moon” swaps rice wine for merlot and the riverbank for “the olive-green lagoon,” maintaining the triangulation (poet–moon–reflection) but changing the water’s social and sensory context; the lunar refusal: “Lunar lips sealed” smartly literalises the impossibility at the heart of the original’s toasting.

Another strong adaptation is “I hang upside down,” which abandons celestial address for embodied botany: “read the brailed ridges of midribs, / netted veins, toothed edges.” The tactile verb “brailed” (evoking touch-reading) recasts “seeing” as learning-by-contact, a formally ethical move in a project negotiating borrowed light. The closing “shift the needle in a compass towards true north / always just ahead” acknowledges aspiration without false arrival.

The closing “At the harbor” completes the arc from homage to inventory. The speaker looks for Li Po “on every knot and thread of his brocaded cloth,” finds only “bent sedge grass,” and lets the absence stand. The catalogue of what remains: “starlit baths, plum blossom rains, / and curved smiles fourteen hundred years old” is graceful but not pious; the past is “freely given; still here,” yet the boat has moved on. The restraint is the point.

Minor Moments of Drift

The war/city pieces can feel somewhat generic in imagery, “Sidewalks strewn with broken glass / unable to reflect moonlight” until the poem’s sound-work (“Panic punctures… / dread pierces…”) sharpens it. I wanted more of that sonic rigour earlier in the stanza, or more concrete urban particularity to resist the timelessness that a moon + glass duet invites.

What the book risks (and largely achieves)

Gonzalez risks two things: writing under the halo of a giant, and translating that halo into a present tense that includes climate grief and municipal precarity. “Instincts” shows how to do both with tonal agility: a real bird’s itinerary, an overwhelmed listener, then a comic, futile directive: “Turn left at the next weather vane.” yelled to the sky. The line lands because it’s specific and because the poem has already earned the right to break its own solemnity.

When the poems keep their hands in the material—kilns, midribs, paddle boats—they feel necessary. When they drift into emblem, the work gestures rather than bears weight. But the centre of gravity holds: by the time we reach the harbour, the sequence has argued, quietly and formally, that homage can be a practice of attention, not a posture.