In Conversation

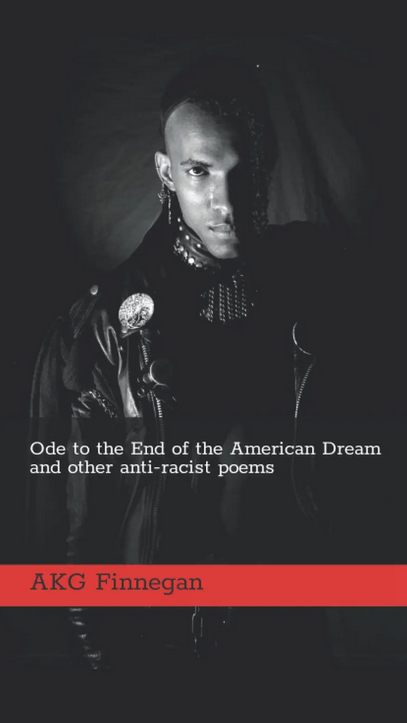

There is no mistaking the voice of Finnegan the Poet. Born and bred in New York City’s fire-lit underground, Finnegan is a performance poet whose work does not ask for your comfort. It devours it. Across decades and continents, his writing has explored race, power, sex, and selfhood with a ferocity few dare to match. His collection Ode to the End of the American Dream and Other Anti-Racist Poems is not just anti-racist. It is anti-lie. Anti-denial. Anti-polish. “The unvarnished truth,” he says. That is the line. Everything else is cowardice.

And Finnegan does not do cowardice.

“It was mental patients who first drew me to poetry”

That line is not performative eccentricity. It is a statement of alignment. Finnegan’s aesthetic does not descend from the ivory tower. It comes from the psych ward, from the edge. “It was mental patients who first drew me to poetry, and it has been my success to express genuine emotion going dark places, which keeps me coming back.” He is not interested in writing for a workshop’s nod. He writes from necessity: emotional, social, and spiritual. Poetry is survival. Poetry is confrontation. Poetry is the record of what we are not supposed to say.

“Inspired is the only condition that functions with writing.” No candles. No silence. No desk-facing-a-window myths. Just inspiration or nothing. That inspiration does not come from Keats or Plath or any anointed lineage. “It wasn’t being inspired by well known poetry that changed the way I write and think. It’s being exposed to concept that placed content over form, that inspires me to fundamentally change the way I write and think.” And that axis—content over form—defines his approach.

“Not get censored or denied”

For Finnegan, writing is a dare. To the reader. To the system. To himself. Every poem in Ode is a raw act of inclusion. “No, I included everything risky and dark. If you can’t handle me at my !%&&^%$ then you shouldn’t be there for my flowers and birds and blue sky either.” He does not believe in withholding to protect the reader or himself. The risk is the point.

And the risk does not just live in what is said. It lives in where the work goes. “Definitely Marginalised,” he says of his place in the poetry world. But that marginalisation only sharpens the blade. “Most of the feedback to my antiracist poetry has been denial, and this but proves the purpose of the work, to open up honest dialogue and not continue with denial as a direction and reaction to the work.”

He knows exactly why the work exists, and who it is up against.

“My instincts tell me not to lie, but my craft must be original and not contrived”

Here, the distinction between instinct and craft becomes a balancing act. Instinct says write it raw. Craft says shape it so it does not collapse. Finnegan holds both. He trusts his gut, but refuses cliché. He is not winging it. He is carving.

And while many poets sweat over drafts, Finnegan takes a different tack. “The poem is done when it is performed before a live audience a few times.” The edit happens in the room. Not in isolation. Not in silence. The audience becomes part of the revision process. Part of the truth test. If it does not land there, it does not live.

He embraces the fallout too. “The responsibility comes with both negative and positive reactions, and a social, political, emotional function of the poem is rather the point, innit?” It is not about universal applause. It is about impact. And sometimes, that impact bruises.

After Ode: toward deeper darkness

Finnegan’s next project is Dark Burning Rain Volumes 1 to 4. He describes it not as a continuation of Ode’s antiracism, but as a descent into something more interior. “Not specifically anti racist works, but focusing on darkness, intensity and self destruction.” The themes are heavier. More personal. Still political, but less public-facing. The risk shifts inward.

And he is not pretending to resolve it. He is still in it. “Working on one thing at a time.” Not chasing approval. Not pivoting to comfort. Just walking deeper into the fire.

Finnegan the Poet’s Ode to the End of the American Dream and Other Anti-Racist Poems is available now. To explore future work, keep an eye out for Dark Burning Rain.

In Critique

Angel Koelmans Gill-Finnegan’s Ode to the End of the American Dream and Other Anti-Racist Poems is not a collection for the faint-hearted or the formally precious. It’s a brutal, rhythmically erratic, and unapologetically profane demolition of institutional racism, internalised trauma, and the hypocrisies of liberal politeness. But underneath the rhetorical pyrotechnics and performative confrontations lies a poet deeply engaged with craft—though not in a conventional, MFA-programme sense.

Take the opening piece, “Some Scenes from the Tales of an Uppity Nigger!”, a fractured monologue that fuses theatrical structure with beat-driven cadences. The repetition of “I am the Ripping Bone” functions as a refrain, anchoring each scene with visceral vulnerability. The syntax is deliberately broken, resisting neat grammar to mirror the poet’s psychological fragmentation. Each scene unravels more personal degradation, racialised violence, and sexual marginalisation, using line breaks and tonal shifts to convey disorientation and survival.

Formally, Finnegan flouts coherence to embrace raw affect. The narrative structure dissolves into impressionistic vignettes, and diction swings violently from lyrical to guttural. This is not for aesthetic effect—it’s a manifestation of trauma that has no elegant expression. In “Creatures”, for instance, enjambment is used aggressively, pushing lines into each other until they blur, mimicking the poet’s descent into self-alienation. The poem culminates in a monstrous self-recognition: “those CREATURES down there / bear not the slightest resemblance to me…” The syntax collapses into anaphora, a hammering, almost biblical reckoning.

Finnegan’s lexicon is intentionally excessive. In “Republican Nightmare!” and “King Kong and the White Woman”, he uses satire like a machete—cutting through America’s political theatre with camp exaggeration and grotesque parody. These poems read like spoken word grenades, lobbed into the genteel dinner party of mainstream poetic discourse. They embrace pop culture and myth not to elevate but to desecrate—King Kong is not a metaphor for Black masculinity; he is its grotesque commodification.

“Ode to the End of the American Dream” is a climax of sorts, structured like a declamatory sermon crossed with a manifesto. The rhythmic pattern here owes more to punk lyrics than to traditional prosody—intentionally rough, meant to be spat rather than read. There’s a rhetorical arc: a condemnation of American hypocrisy through anaphora (“Good Morning America”), amplified by enjambment and line-staggering that mimics breathlessness and fury.

What falters is occasionally the overextension of these devices. The unrelenting pace and density can flatten nuance; the reader is bludgeoned rather than seduced. In poems like “Tourist Attractions from the Land of the Cartoon Nigger”, the cacophony of all-caps, slashes, and exclamations risks alienating the very intimacy the speaker otherwise crafts so powerfully. But this might be intentional—Finnegan writes not to invite, but to indict.

In sum: this is high-risk poetry that refuses polish in favour of precision—emotional, racial, sexual. Finnegan’s form is anarchic, but not arbitrary. It serves the fury, the satire, the confessions, the screams. This is not posturing; it’s purging. Whether or not one aligns with his poetics, it is undeniable: the form carries the weight.